But over the past four days of twice-daily two-hour sessions, Olsen has shown just what a miracle worker a top coach can be. Thanks to a series of progressive drills, in-the-pool demonstrations, computerized stroke analysis and spot-on analogies, he has helped me reprise “Pygmalion” in the pool.Sometime on the second day, I had my breakthrough. I had just finished a drill Jon had invented to show how you can keep your arms in a fixed position but still pull water by rolling side to side. The drill had yet to be named, so I dubbed it the landed tuna.

As I caught my breath afterward, Olsen explained the arm positions he wanted me to assume during two key phases of the stroke: the underwater catch (where your arm and hand are outstretched in front of you and sink slightly before grabbing an initial “hold” on the water) and the recovery (where your opposite arm swings forward through the air before re-entering the water).

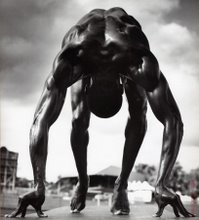

To explain the catch, Olsen described how he cleaned up logs after a hurricane. “This is how I want your catch to look,” he said, mimicking the curled-over, high-elbow position he used to reach over a log and scoop it up. I visualized my underwater arm moving from a sinking horizontal spear to this high-elbow, log-grappling configuration.

For the recovery phase, he had another apt analogy: a backhoe. At this, Olsen pointed his out-of-the-water elbow skyward while letting his forearm and fingertips hang down in a loose, relaxed posture. Pantomiming a backhoe, he moved his elbow forward while swiveling and extending his forearm until the fingertips naturally speared the water surface.

In Olsen’s view, efficient swimming is like rowing a single scull: a moment of explosive propulsion followed by a nearly effortless, recuperative glide. Plenty of swimmers focus on maximizing propulsion but ignore the glide. The fastest swimmers are not the most powerful but the most efficient.

As I stroke-glided, stroke-glided toward the wall on my final 150 meters, somehow everything was clicking. But I was officially dead, my limbs leaden with lactate.

Exhausted, I was no longer capable of thinking about what I was doing here, but it felt right — like when you finally relax your eyes enough for one of those 3-D pictures to snap into recognition.

“Your stroke held up pretty good,” Olsen said, beaming a little. “How’s it feel?”

When I was capable of speaking again, I started to blurt out, “Almost natural,” but caught myself. “Less unnatural.”

He smiled encouragingly. “The best time to fight old habits and make corrections is when you’re going smooth and slow,” he said. “Really think about what you’re doing during warm-up or warm-down or easy swims between hard sets. But when you’re doing hard sets or racing, turn the brain off and just let your body go on its own.” The new stroke, he said, will eventually become second nature.

After two months of practice, I find myself on the blocks at a meet in Virginia, awaiting the start of the 100-yard freestyle. It’s not my best competitive distance, but it’s the benchmark by which I measure my downward slide toward dotage.

My brain, as Olsen recommended, is completely shut off now, although the reason is less volitional than viral. I’ve never had a cold this bad at any swimming meet in my entire life. My original goal of breaking 54 seconds has changed drastically. I just want to finish without having to be fished out of the pool.

Even after a lifetime of “Rocky” movies, I can’t quite believe what happens next, because it has such a feel-good unreality to it: 52.69 seconds after the start, I hit the touchpad. I have to look at the clock three times to convince myself I’m not hallucinating.

This is the fastest I’ve swum in five years — and less than a half-second off my high school best. Bless you, Jon Olsen!

If I can just hold on to this speed a little longer, a world record in the 100-to-104 age group looks inevitable.

GO HERE TO STOKE YOUR STROKE

THE RACE CLUB

Specializing in “creative training for fast swimming,” the Race Club accommodates swimmers 8 years old and up year-round. The camps usually run from one to six days, but you can customize your own (starting at $265, not including hotel). theraceclub.net.

ADVANCED SWIM CAMPS

Five-day camps are held in Tampa and San Francisco for swimmers as young as 5. Twice-daily training sessions feature frame-by-frame video analysis to cut stroke count by a guaranteed 30 percent ($2,975, plus meals and hotel). somaxsports.com/swimcamp.htm.

LA LOMA ALTITUDE TRAINING CENTER

Located 6,233 feet above sea level in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, La Loma has played host to club swimmers as well as Olympians like Michael Phelps and Kaitlin Sandeno ($55 per day, including meals and lodging). Altitudeswimming.Com.

TOTAL IMMERSION

Specializing in stroke improvement, T.I. conducts hundreds of workshops around the country each year as well as an open-water swim camp in the Bahamas during the winter (starting at $495 for a weekend workshop). totalimmersion.net.

FASTER FREESTYLE

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO JON OLSEN

1. Keep your head down. Forget the old idea of keeping your head high enough so that the water hits you in the forehead. You’ll move faster and with less resistance by keeping your head on an even plane with your body, as if you were standing and looking straight ahead.

2. Think scull, not plow. As much as possible, try to stay horizontal in the water. Good head position will definitely help. You don’t want your feet and hips to drop and drag, which only makes you plow through the water and, in effect, swim uphill. Avoid arching your back, and try to stay flat, long and streamlined — like a single scull skimming through the water. When your body position is right, it can almost feel like you’re swimming downhill.

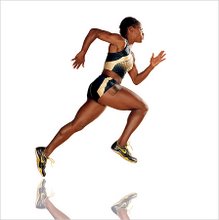

3. Recruit the core. Coordinate your kick, body rotation, catch and pull to allow your core muscles to do as much of the heavy lifting as possible. Relying too much on your arms and shoulders will make you slower and more prone to injury.

4. Avoid crossing over. Imagine a line bisecting your body vertically. Many swimmers, especially when breathing, have a tendency to let their hands cross this line during the pull.

5. Finish your stroke. Pushing up or down against the water wastes energy and contributes nothing. Make sure your propulsive efforts keep you moving in a horizontal vector. From the initial catch to the final push of each arm stroke, keep your fingertips pointed toward the bottom of the pool. As your underwater hand moves in front of your head, and then parallel to your body, and then back toward your thigh, your wrist should adjust to ensure that your palms and fingertips pull, then push, the water horizontally toward your feet.

As I caught my breath afterward, Olsen explained the arm positions he wanted me to assume during two key phases of the stroke: the underwater catch (where your arm and hand are outstretched in front of you and sink slightly before grabbing an initial “hold” on the water) and the recovery (where your opposite arm swings forward through the air before re-entering the water).

To explain the catch, Olsen described how he cleaned up logs after a hurricane. “This is how I want your catch to look,” he said, mimicking the curled-over, high-elbow position he used to reach over a log and scoop it up. I visualized my underwater arm moving from a sinking horizontal spear to this high-elbow, log-grappling configuration.

For the recovery phase, he had another apt analogy: a backhoe. At this, Olsen pointed his out-of-the-water elbow skyward while letting his forearm and fingertips hang down in a loose, relaxed posture. Pantomiming a backhoe, he moved his elbow forward while swiveling and extending his forearm until the fingertips naturally speared the water surface.

In Olsen’s view, efficient swimming is like rowing a single scull: a moment of explosive propulsion followed by a nearly effortless, recuperative glide. Plenty of swimmers focus on maximizing propulsion but ignore the glide. The fastest swimmers are not the most powerful but the most efficient.

As I stroke-glided, stroke-glided toward the wall on my final 150 meters, somehow everything was clicking. But I was officially dead, my limbs leaden with lactate.

Exhausted, I was no longer capable of thinking about what I was doing here, but it felt right — like when you finally relax your eyes enough for one of those 3-D pictures to snap into recognition.

“Your stroke held up pretty good,” Olsen said, beaming a little. “How’s it feel?”

When I was capable of speaking again, I started to blurt out, “Almost natural,” but caught myself. “Less unnatural.”

He smiled encouragingly. “The best time to fight old habits and make corrections is when you’re going smooth and slow,” he said. “Really think about what you’re doing during warm-up or warm-down or easy swims between hard sets. But when you’re doing hard sets or racing, turn the brain off and just let your body go on its own.” The new stroke, he said, will eventually become second nature.

After two months of practice, I find myself on the blocks at a meet in Virginia, awaiting the start of the 100-yard freestyle. It’s not my best competitive distance, but it’s the benchmark by which I measure my downward slide toward dotage.

My brain, as Olsen recommended, is completely shut off now, although the reason is less volitional than viral. I’ve never had a cold this bad at any swimming meet in my entire life. My original goal of breaking 54 seconds has changed drastically. I just want to finish without having to be fished out of the pool.

Even after a lifetime of “Rocky” movies, I can’t quite believe what happens next, because it has such a feel-good unreality to it: 52.69 seconds after the start, I hit the touchpad. I have to look at the clock three times to convince myself I’m not hallucinating.

This is the fastest I’ve swum in five years — and less than a half-second off my high school best. Bless you, Jon Olsen!

If I can just hold on to this speed a little longer, a world record in the 100-to-104 age group looks inevitable.

GO HERE TO STOKE YOUR STROKE

THE RACE CLUB

Specializing in “creative training for fast swimming,” the Race Club accommodates swimmers 8 years old and up year-round. The camps usually run from one to six days, but you can customize your own (starting at $265, not including hotel). theraceclub.net.

ADVANCED SWIM CAMPS

Five-day camps are held in Tampa and San Francisco for swimmers as young as 5. Twice-daily training sessions feature frame-by-frame video analysis to cut stroke count by a guaranteed 30 percent ($2,975, plus meals and hotel). somaxsports.com/swimcamp.htm.

LA LOMA ALTITUDE TRAINING CENTER

Located 6,233 feet above sea level in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, La Loma has played host to club swimmers as well as Olympians like Michael Phelps and Kaitlin Sandeno ($55 per day, including meals and lodging). Altitudeswimming.Com.

TOTAL IMMERSION

Specializing in stroke improvement, T.I. conducts hundreds of workshops around the country each year as well as an open-water swim camp in the Bahamas during the winter (starting at $495 for a weekend workshop). totalimmersion.net.

FASTER FREESTYLE

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO JON OLSEN

1. Keep your head down. Forget the old idea of keeping your head high enough so that the water hits you in the forehead. You’ll move faster and with less resistance by keeping your head on an even plane with your body, as if you were standing and looking straight ahead.

2. Think scull, not plow. As much as possible, try to stay horizontal in the water. Good head position will definitely help. You don’t want your feet and hips to drop and drag, which only makes you plow through the water and, in effect, swim uphill. Avoid arching your back, and try to stay flat, long and streamlined — like a single scull skimming through the water. When your body position is right, it can almost feel like you’re swimming downhill.

3. Recruit the core. Coordinate your kick, body rotation, catch and pull to allow your core muscles to do as much of the heavy lifting as possible. Relying too much on your arms and shoulders will make you slower and more prone to injury.

4. Avoid crossing over. Imagine a line bisecting your body vertically. Many swimmers, especially when breathing, have a tendency to let their hands cross this line during the pull.

5. Finish your stroke. Pushing up or down against the water wastes energy and contributes nothing. Make sure your propulsive efforts keep you moving in a horizontal vector. From the initial catch to the final push of each arm stroke, keep your fingertips pointed toward the bottom of the pool. As your underwater hand moves in front of your head, and then parallel to your body, and then back toward your thigh, your wrist should adjust to ensure that your palms and fingertips pull, then push, the water horizontally toward your feet.

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder