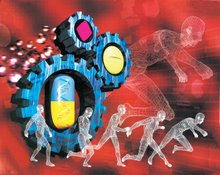

Pharmacological cheating in sports is not a new phenomenon. Unfortunately, the modern era has witnessed explosive growth in new and different ways to achieve false victory. Advances in biochemistry, medicine, and other fields have benefited humanity in countless ways. Sadly, however, some have abused these advances for, “pursuit of victory at all cost”. A recent article by Dr. Timothy Noakes (1) highlights the breadth and depth of the problem. He discusses several “cheating venues”, but for this article I wish to focus on one, erythropoietin.

Erythropoietin (pronounced, ah-rith-ro-poy-tin, and abbreviated, EPO) is a relatively recent entry into the deceitful pursuit of glory. EPO is a protein hormone produced by the kidney. After being released into the blood stream it binds with receptors in the bone marrow, where it stimulates the production of red blood cells (erythrocytes). Medically, EPO is used to treat certain forms of anemia (e.g., due to chronic kidney failure). Logically, since EPO accelerates erythrocyte production it also increases oxygen carrying capacity. This fact did not long escape notice of the athletic community.

Blood doping is the process of artificially increasing the amount of red blood cells in the body in an attempt to improve athletic performance. In the past this was accomplished by transfusion. The athlete would “donate” a unit of blood into storage and then 3 weeks later, after the body had completely replaced the blood loss, transfuse the unit back into the body. This would occur just before a big race, effectively giving the athlete an “extra” unit of blood. This enables performance improvements in endurance sports because of the extra oxygen carrying capacity. The practice has been outlawed. Not just because it is unfair but because of the dangers involved.EPO has put a whole new spin on blood doping. No need for messy transfusions, just shoot up with EPO to increase your circulating erythrocyte mass. Until recently accurate testing has been difficult because the recombinant human EPO made in the lab is virtually identical to the naturally occurring form and there are no firmly established normal ranges for EPO in the body. The only previously available route to curtail cheating for sports governing bodies was to ban an athlete if the hematocrit (see side bar) level was too high (e.g., above 50%). Thus, over the past 10 – 15 years some athletes chose to cheat because, as long as they kept their hematocrit levels below 50%, there seemed little risk of getting caught. Of course the other way to get caught was highlighted in the disastrous 1998 Tour de France. Several team doctors and personnel from several teams were caught red-handed with thousands of doses of EPO and other banned substances. Ultimately about 50% of the teams withdrew from the race – either for cheating or in protest. Fortunately, testing technology has now caught up and promises to stem the tide of abuse. There is now an accurate urine test that can detect the differences between normal and synthetic EPO. This test is now the standard and was the sole means to detect for EPO use in the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. The reliability of this test helps explain the cascade of athletes who have been caught and, subsequently, banned from competition. This surge in positive tests will likely decline as the “word” gets out and EPO use declines -- at least until someone figures out a work-around. Of course, there is always the next great pharmacologic or genetic cheat just lurking around the corner to consider.

Blood doping is the process of artificially increasing the amount of red blood cells in the body in an attempt to improve athletic performance. In the past this was accomplished by transfusion. The athlete would “donate” a unit of blood into storage and then 3 weeks later, after the body had completely replaced the blood loss, transfuse the unit back into the body. This would occur just before a big race, effectively giving the athlete an “extra” unit of blood. This enables performance improvements in endurance sports because of the extra oxygen carrying capacity. The practice has been outlawed. Not just because it is unfair but because of the dangers involved.EPO has put a whole new spin on blood doping. No need for messy transfusions, just shoot up with EPO to increase your circulating erythrocyte mass. Until recently accurate testing has been difficult because the recombinant human EPO made in the lab is virtually identical to the naturally occurring form and there are no firmly established normal ranges for EPO in the body. The only previously available route to curtail cheating for sports governing bodies was to ban an athlete if the hematocrit (see side bar) level was too high (e.g., above 50%). Thus, over the past 10 – 15 years some athletes chose to cheat because, as long as they kept their hematocrit levels below 50%, there seemed little risk of getting caught. Of course the other way to get caught was highlighted in the disastrous 1998 Tour de France. Several team doctors and personnel from several teams were caught red-handed with thousands of doses of EPO and other banned substances. Ultimately about 50% of the teams withdrew from the race – either for cheating or in protest. Fortunately, testing technology has now caught up and promises to stem the tide of abuse. There is now an accurate urine test that can detect the differences between normal and synthetic EPO. This test is now the standard and was the sole means to detect for EPO use in the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. The reliability of this test helps explain the cascade of athletes who have been caught and, subsequently, banned from competition. This surge in positive tests will likely decline as the “word” gets out and EPO use declines -- at least until someone figures out a work-around. Of course, there is always the next great pharmacologic or genetic cheat just lurking around the corner to consider.

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder